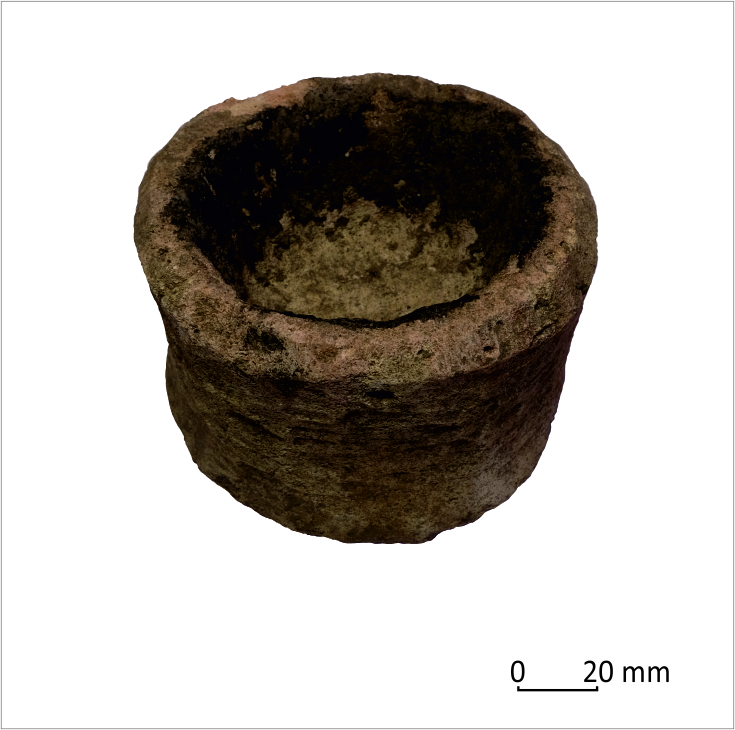

A cresset, or lamp, found during archaeological work for The King’s School at Dulverton House, Gloucester Cathedral probably dates from the medieval period when the site was part of the Abbey of St Peter, now Gloucester Cathedral. On this complete example the carved limestone had been scorched by the heat of the lamp with a thick black residue adhering around the inner walls.

The cresset has been studied by expert Dr Ruth Shaffrey who has been looking at how these lamps were made and used; the discovery of a cresset with apparent combustion residue was too good an opportunity to be missed, and promised to tell us what was used as fuel. Dr Shaffrey commented ‘this was a really exciting find. As one of only c100 stone cressets of simple block form currently recorded from Saxon and medieval England and one of only a handful with significant residue deposits, we are grateful that King’s appreciated the significance of it and funded the residue analysis’.

Lipid analysis of this burnt residue by Dr Julie Dunne and colleagues at the Organic Geochemistry Unit, University of Bristol, showed that the residue derived from a mix of ruminant animal fats (probably tallow) with up to 50% non-ruminant (e.g. pork) fat. Different fats have different qualities when burnt: beeswax being the best and cleanest (and often reserved for the church), whilst using pure tallow gave a putrid stench and offensive smoke, a point noted by Samuel Pepys in the 17th century. These characteristics would have been well understood by the lamp’s users and the mix of fats suggests a blending, or different fuels at different times. Dr Dunne said ‘these exciting results confirm the importance of future analysis of such vessels to better understand what types of fats were used in them’.

Although several clay lamps have undergone residue analysis, this is the first stone cresset to be subjected to this technique, which allows us to confirm that small stone vessels were used directly as lamps and that they did not always contain an inner ceramic vessel as was sometimes the case.

Chiz Harward, who led the dig by Urban Archaeology, said that whilst the cresset was found in a post-medieval context, its findspot by the arches of St Peter’s Infirmary strongly suggests that it is from the abbey:

‘This crudely carved object, encrusted with its burnt residue, conjures up images of monks making their way to the church in the dead of night, casting a flickering light on the abbey’s past’

The Dulverton House cresset may well have illuminated access to the church for the regular night-time offices; lamps and lanterns were a feature of monastic buildings and are mentioned several times by Lanfranc in his 11th century ‘Monastic Constitutions’, and in the 16th century ‘Rites of Durham’ which describes a lantern ‘filled with tallow and euerye night one of them was lighted when the day was gone, and did burne to giue light to the monkes at midnight when they came to mattens’. Stone lanterns survive at St Peter’s Gloucester and Glastonbury Abbey, with cressets found in monastic sites such as Fountains Abbey, but examples with burnt residue are very rare. Most medieval lamps would have been ceramic, with stone very much the exception. Many are crudely made, and appear to have been made on an ad hoc basis rather than as a workshop industry, perhaps using offcuts from the masons’ yards, nevertheless through the application of lipid analysis they continue to shine a light on the past.

A research note on the cresset has just been published in the journal Medieval Archaeology https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00766097.2022.2129702