One morning earlier this month, I pulled on my boots and walked from the village of Askham near Penrith in Cumbria to Lowther Castle, formerly the seat of the earls of Lonsdale. The two aren’t far apart, but we deliberately took a somewhat roundabout route across Lowther’s parkland, which looks like (but isn’t) the work of “Capability” Brown.

Early morning mist having given way to autumn sunshine, there were brilliant views to be had of the mountains to the north, one of which I took, possibly wrongly, to be Blencathra, the fell controversially sold by the present earl to an “unnamed party” last July, and of the Lonsdale mausoleum, which stood rather nobly on the ridge above us.

What we were really doing, however, was delaying for as long as possible the wondrous moment when we would catch sight of the castle itself, a gothic revival palace by Robert Smirke that was painted by Turner, and celebrated in poems by Wordsworth and Southey.

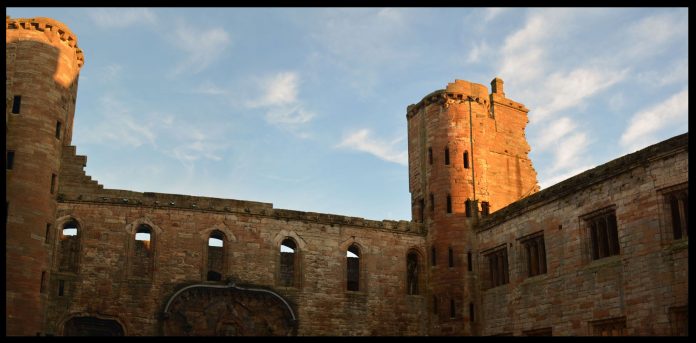

Lowther is a ruin – the 5th earl having blown his funds on liveried footmen and other extravagances, it was abandoned in 1935 and its roof removed in 1957 – and its silhouette is straight out of a novel by Mrs Radcliffe. A gasp-inducing confection of towers and lancet arches, you would not be surprised to meet some headless horseman racing towards you in its approaches, even in bright daylight.

Visitors can press their noses up against the boundary wall of this world within a world for free. But to visit its “lost” Edwardian gardens, now being slowly restored with financial help from various regeneration funds, you must buy a ticket from a volunteer – your passport to a ghostly verdancy of long-forsaken iris gardens, crepuscular Japanese ponds and a deserted, Swiss-style summerhouse that is all the more eerie for being so kitsch.

Alone in its woodland, time concertinas, the present fading quickly to grey. The scalp prickles, the hairs on your neck rise. Beautiful and mysterious. I knew in an instant it would join the list of places I wander in my mind’s eye when life is getting me down.

Should “heritage” be prescribed? The evidence is mounting that it should be. The 2014 edition of Heritage Counts, an annual survey of the state of England’s historic environment carried out by English Heritage, has so far been little reported. But take a look and it’s there in black and white. This year’s survey attempts to work out the true value of heritage to the public.

Although I confess to bristling slightly at the idea of putting a monetary value on things that are, to me, priceless, its conclusion that visits to places such as Lowther Castle make people happy to the tune of £1,646 a year is impossible to ignore. (This is the sum that you would need to take away from a person to return him to the level of wellbeing he would have had without any such day trips.)

It is, moreover, a contentment that extends both to those who volunteer in such places (work that is fulfilling and which brings them increased “social contact” – ie new friends) and to those who live nearby (90% of those surveyed agreed that investment in their local historic environment made their area a better place; 87% believed it improved quality of life).

The report doesn’t say so, but this sense of wellbeing extends even to its own pages. I can’t remember the last time I read an official document so full of inspiriting stories: the “pocket park” created on a brownfield site by people in Hackney with help from the National Trust’s Sutton House nearby; the work of volunteers to help preserve for future generations the Hartley’s Village near Aintree, Liverpool, which was built in 1886 by William Hartley, the jam-maker; a project at the Jubilee Colliery, Oldham, that enabled volunteers from nearby schools to learn archaeological skills, the better to tackle the site’s decline.

All this is deeply satisfying, but is it surprising? Not to me, it isn’t – and not only because I’m the kind of person who spends quite a lot of her free time touring Victorian town halls and dilapidated postwar churches. Last Sunday in the Observer, I wrote a long piece about Stoke-on-Trent, in which I suggested that things in the city, having been grim for a while, were beginning to get better. Along the way, I made the point that only rarely is knocking stuff down the best way of improving a place, that leaving good structures to rot is a crime, and that Stoke is lucky enough to be in possession of an exceptionally gorgeous cache of historic buildings.

The response to this was amazing: the happiest I’ve had in a 23-year career as a journalist. Yes, one or two people asked why I’d ignored the city’s food banks (answer: that was not the story I was trying to write). But most got in touch to say how cheering they’d found the piece, how hopeful. On BBC Radio Stoke, a presenter asked if my “friends in London” were now likely to visit. I was, I must admit, a little bewildered by this question. Why would someone not want to see the Bethesda Chapel, the Wedgwood Museum, the Middleport Pottery? That, to me, would be their loss.

These two things coming together – my report on Stoke and that of Heritage Counts – have crystallised a couple of things for me.

The first is my belief that people long for good news, and that when they hear it, they feel uplifted, even galvanised. This is something our politicians would do well to remember, locked as they are in a spiralling circle of doom.

The second is that caring about buildings of whatever kind (and let it be known that I’m not some Prince Charles-style nostalgist; I love brutalism, too, done well) is another way – perhaps the very best way we have – of caring about people.

This connects to housing, of course, but it has also to do with what we’ve learned to call “heritage”. Good and lovely buildings gladden the heart; their aesthetic pleasures make people feel substantively better.

More than that, they provide a healthy sense of perspective. By connecting us subtly to the past, they somehow lighten the load of the present. And which of us doesn’t sometimes desperately need that?

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.