- Location: Castle Hill Country Park, Astill Lodge Road, Beaumont Leys, Leicester LE4 1ED

- Walk length: 1 mile / 1.5 km

- Gradient: Moderate to steep with a few steps, grass paths, can be wet underfoot

- Parking: Car park at community centre on Astill Lodge Road 100m east of park entrance

Download a printable version of the walk here (pdf, 1.69mb).

Welcome to Castle Hill Country Park. This walk will guide you around Castle Hill, the main archaeological site in the park, and tell you what is known so far about its history and archaeology.

Enter the park at the entrance on the corner of Astill Lodge Road and Kingsbridge Crescent

1. Castle Hill Country Park

The park was created in 1984 to protect the enigmatic earthwork at Castle Hill from the encroaching development of Beaumont Leys. Today, the park covers some 250 acres of grassland, plantation and broad-leaved woodland to either side of the A46, between the settlements of Beaumont Leys and Anstey. You can find out more about the park here.

Castle Hill has been the source of much speculation since attention was first drawn to it in the late 19th century. It was shown as a ‘supposed encampment’ on early Ordnance Survey maps of Leicestershire and in 1891, one local historian, F.T. Mott, suggested that it might be an Iron Age hillfort. Better understanding of the site was hindered through much of the late 19th and 20th century, however, by its incorporation within the Beaumont Leys Sewage Farm. Today it is generally recognised as a medieval estate centre associated with the Knights Hospitaller.

To find answers, in 2016-18 University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) partnered with Leicester City Council to run a community excavation at Castle Hill. This was the first investigation of the monument and gave volunteers a hands-on opportunity to learn more about the history of their local area. The excavation was part of the City Council’s Story of Parks project, a two-year Heritage Lottery-funded venture to collect and celebrate the history of Leicester’s parks through the stories and memories of the people using them.

Follow the path down the hill keeping the hedge to the right.

2. The Community Orchard

On your left as you walk down the hill is the park’s community orchard. This was planted in 2005 and aims to re-establish a traditional orchard with a wide variety of native fruit trees including many traditional Leicestershire varieties.

An orchard was first mentioned in the possession of the Knights Hospitaller in 1338 and in 1686 an estate map of the Beaumont Leys estate still labelled the field to the north as ‘The Orchard’.

Pass through the trees and across the bridge into the grassy glade beyond.

3. Prehistoric and Roman activity

Fieldwalking in fields around the park has recovered a scatter of worked flint of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age date, as well as Iron Age pottery, showing that people have used this landscape for more than 10,000 years.

A sizeable well-defined scatter of Roman pottery and tile has also been found in this glade, possibly identifying the site of a Roman farmstead surrounded by fields. A substantial quantity of iron slag also suggests that the working of iron was taking place nearby.

Bear right, then turn right through the gate, down the steps and across the bridge into the next field.

4. The medieval manor

You have now entered the Scheduled Monument, given statutory protection in 1980. The hill in front of you is a spur of high ground projecting from a broad ridge running south-west to north-east between the River Soar and the Rothley Brook.

By the medieval period, this ridge was covered by a mosaic of oakwood, pasture and heath (much like the park’s appearance today), which was exploited for timber, for grazing and for hunting and recreation. After 1066, Leicester Forest was under the control of Leicester’s new Norman overlord, Hugh de Grandmesnil and his successors, the earls of Leicester. Sometime around 1240, the 6th earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort, granted land around Castle Hill to the Catholic militant Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller.

The Knights Hospitaller was founded in the early 12th century, following the First Crusade, to provide care for sick, poor and injured pilgrims and to defend the Holy Land. To support its activities, the Order relied heavily on income from its estates and churches in western Europe. In Britain, the Order’s possessions were divided into bailiwicks, each administered from a preceptory. As well as generating revenue, each preceptory would have provided hospitality for travellers and served as a religious house so that its brethren could lead a life in accordance with the rules and statutes of the Order. By the 14th century there were 37 preceptories in England.

In Leicestershire, the baulk of the Hospitaller possessions, including Castle Hill, were administered from their preceptory at (Old) Dalby, 11 miles away. Our best insight into their land here comes from a 1338 survey. Beaumont was listed as a dependant manor of Dalby with a house, 220 acres of arable land, meadows, pasture and an apple orchard (about 960 acres altogether), managed by a bailiff and a wood keeper (indicating that there was still enough woodland to need management). It was probably established as a sheep farm and in 1306 the brother of the ‘Master of Beaumont’ got into trouble with the burgesses of Leicester for the illegal sale of wool fleece from Beaumont. Little else is known about the manor. A fishpond was mentioned in the 15th century but in 1482 the Hospitallers gave the site to King Edward IV in exchange for the more profitable rectory of St Botolph at Boston in Lincolnshire.

Turn left, bear left as the path forks and follow it around the foot of the hill until you reach the large earth bank at the north end of the field.

5. The fishpond

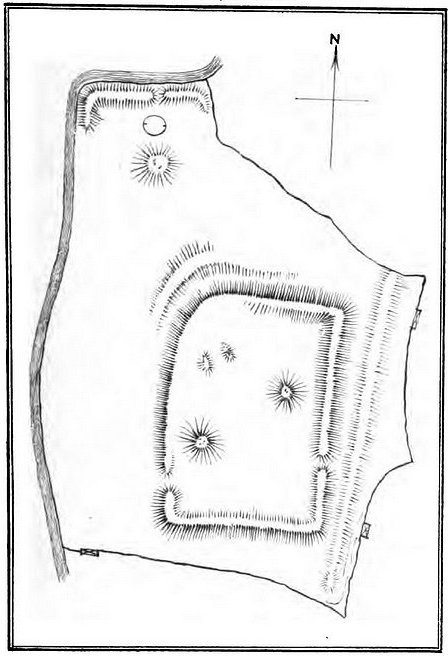

The low-lying ground you have just walked across is the remains of a large fishpond. In the medieval period, the 100m long, 3m high earth bank in front of you dammed the stream flowing down the valley creating a pond which was at least 100m long and 75m wide. The old stream can still be seen as a dip crossing the path and a nearby circular mound may have been an island in the pond.

Fish was an important part of the medieval diet, especially in religious communities where eating meat was prohibited on certain days of the year, and in the winter when other fresh meat was scarce. Freshwater fish was also valued for the status its costly production brought. Once a year, probably in the spring, the pond would have been drained and cleared. This meant that it needed to be managed by a system of sluices, channels and dams which could control fluctuations in water flow and prevent flooding – an expensive endeavour to properly maintain. The main species of fish kept were probably eel, tench, pickerel, bream, perch, and roach.

Most fishponds fell out of use during the post-medieval period, although some were re-used as ornamental features in 19th and early 20th century landscape parks or gardens. Here, probably after 1686 as it is shown on an estate map of that date, the dam was deliberately cut through to drain the pond.

Turn right and follow the path up the hill into the field (NOT the path which continues to follow the hedge).

6. The ridge and furrow

As you climb the hill, above the fishpond, the hillside is covered with long parallel lines of shallow earthworks. These are not usually visible, especially when covered with long vegetation, but can be easily identified using LiDAR. These are the remains of ridge and furrow, created by a system of single-sided ploughing used in Europe in the medieval period. Repeated ploughing would pile earth up into a series of ridges separated by shallow furrows. They show where there was arable field around the manor enclosure.

7. The outer earthwork

As you reach the top of the hill you will notice that you have walked over a bank and ditch. This is the outer earthwork of the medieval manor, a large sub-rectangular enclosure measuring 200m by 150m. The enclosure is formed by a bank measuring up to 1.5m high in places and an outer ditch measuring 5m wide and about 0.5m deep today but originally over 2m deep.

Excavations have found that the bank was carefully built up with earth and stone, presumably dug out of the ditch, but there was no defensive wall. Instead, the bank probably supported a wooden fence or hedge which would have stopped livestock and casual intruders wandering into the enclosure (it was not a castle, despite its name which is a bit of a red herring). So far, there is no indication that the bank and ditch predate the 13th century and it is unlikely that the enclosure was an Iron Age hillfort.

8. The manor house

As you move into the enclosure, on your left, excavations have found a large medieval building, probably the manor house itself. Surviving stone footings show that it measured 8m wide by 15-20m in length. It was timber framed with a slate roof capped with expensive decorative green-glazed ridge tiles. The wall timbers rested on a shallow stone plinth and inside was a central hearth which suggests that part of the building was a hall which was open to the roof. The Guildhall in Leicester, built in the late 14th century, gives us a good idea of what this building might have looked like.

Pottery from the site dates to between the 13th and mid-15th century, consistent with the period the Knights Hospitaller held the manor (1240-1482). So far, excavations have found no evidence of earlier or later occupation, and the site appears to have been abandoned as early as 1450, several decades before the Hospitallers gave the manor to the king.

The floor inside the hall was earth but was at some point was replaced with rough stone paving. Outside were paved and cobbled yards. A stone-lined well was immediately east of the hall and further buildings may have surrounded a yard to the west.

A large quantity of iron slag and hammerscale (the sparks from hitting molten metal) was found covering the hearth. This indicates that a blacksmith was working inside the hall shortly before it was demolished. If this was once the manor house, this shows that the building’s role changed towards the end of its life, moving from high-status residence to a lower status service role.

During the clearance of the site in the late 15th century, the well was filled in with rubble from the hall, including a well-preserved group of building timbers which had lodged in the well shaft and had survived because of the waterlogged conditions.

Follow the path until you reach a crossroads.

9. The central mound

To your right is a small circular mound, often only visible when the grass is cut. It is 12m in diameter and 1m high. Presently, it is unclear what the mound may have been or when it dates too. It could be a prehistoric burial mound. However, there are other interpretations including the mound for a medieval post-mill or even a prospect mound in the post-medieval deer park. Further investigation is needed to learn more.

Turn left and follow the path until you reach another crossroads.

10. The second mound

To your right, this second mound and the hollow to the south have been excavated. Geophysical survey suggested that the hollow might contain a rectangular structure, perhaps a building, but excavation found it to be a pond with the mound formed from the earth dug out of it. The ‘structure’ was stones lining the pond edge, probably to stop it becoming churned up by livestock. An exact date has not been established but it had silted up before the 18th century. The remaining boggy hollow was later adapted as an evaporation pool for the 19th-century sewage farm.

Following Edward IV’s acquisition of Beaumont in 1482, the king cleared the buildings from the site and enclosed part of the manor with a pale as a deer park. A commission of Henry VIII in 1524 found the park to be well-stocked with at least 800 deer but two years later it was disparked and most of the grazing given over to the people of Leicester for their domestic stock.

This pond was most likely a watering hole for deer or livestock during this period of the site’s history although it cannot be ruled out that it was much older, perhaps contemporary with the medieval manor.

Turn right and follow the path across the enclosure, cross the bank and ditch and follow the path downhill.

11. The entrance

As you reach the south-east corner of the site, to your left, the eastern bank of the enclosure flattens. Here the bank is 12m wide but less than half a meter high, twice the width and half the height of the bank elsewhere. Excavation of the ditch outside the bank found a 6m wide break in its line creating a causeway into the site from the high ground to the east. A spread of stones in the entrance may have been the remains of a paved roadway across the causeway. So far, this is the only known entrance to the enclosure but there were probably entrances on the other sides which would have allowed better access to the fishpond and the valley meadows to the north. This entrance was likely used to reach the upland farmland, pasture and woodland to the east and south.

The ditch started to silt up during the medieval period and there was no evidence that it was repeatedly dug out and kept clean. Eventually it filled with clay and stone which had eroded from the adjacent bank. In the 19th century, a ceramic drain was inserted down the length of the trench, possibly to improve drainage of the adjacent farmland or as part of the sewage farm.

Follow the path through the hedge and you will reach the park entrance where the walk started.

12. The sewage farm

As you walk around Castle Hill, you may come across several brick and concrete structures. These are the remains of the Beaumont Leys Sewage Farm. In the late 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I granted the manor, by then called Beaumont Leys, to Sir Henry Skipworth and it was divided into several arable and pastural farms with a few remnant areas of woodland. Finally, over the period 1885-1901, the entire estate was sold to the Leicester Corporation for use as a sewage disposal works linked to an agricultural scheme known as the City Farms.

Leicester’s rapidly expanding urban population in the latter half of the 19th century necessitated improved sewage systems. The Leicester Corporation pumped sewage to Beaumont Leys via pipes and culverts from the Abbey Pumping Station on Corporation Road and used the earthwork at Castle Hill and the surrounding fields to hold and dry sewage. Photographs of the site during this period give the impression that extensive damage was done by the digging of sewage channels and evaporation pools. However, excavation has shown that many of these were superficial or reused existing features and had caused very little damage to the underlying archaeology. The sewage farm closed in 1964.

We hope you have enjoyed your walk. Castle Hill is an exceptionally well preserved rural medieval site which has escaped significant damage from modern ploughing because of its later use as a deer park, pasture then sewage farm. Archaeological work here is important. There have been few excavations of Hospitaller sites in Britain and the work at Castle Hill has added valuable new insights into how the Hospitallers lived and operated in England. Work has also established how vulnerable the monument is and has aided Leicester City Council’s efforts to preserve it for the future.

Find out more about the archaeological work in the park here.

This walk was created for the CBA Festival of Archaeology’s Online and Active programme by University of Leicester Archaeological Services and Blaby District Council.

Source: ULAS