Over the last five years, ULAS has been busy investigating Leicester’s waterside, a large area of the historic city centre stretching 400m along the east bank of the River Soar and the Grand Union Canal from Bath Lane to Frog Island. A once busy area, characterised by manufacturing, it has suffered decline over the last 30 years and has been in need of regeneration. Now, Leicester City Council is transforming the area into a new neighbourhood for people to live and work. Work started in 2015, when ULAS excavated a well-preserved Roman building at Friar’s Mill. Now, further excavations have revealed more evidence of the Roman and medieval town. Site Director, Steve Baker reports:

The team worked in the footsteps of the demolition company removing the numerous factories that sprawled across this area of the city. Some of the site was dominated by remnants of the long-demolished Great Central Railway viaduct, which both destroyed all archaeological remains in the footprints of its foundations and, paradoxically, preserved them beneath the span of its arches.

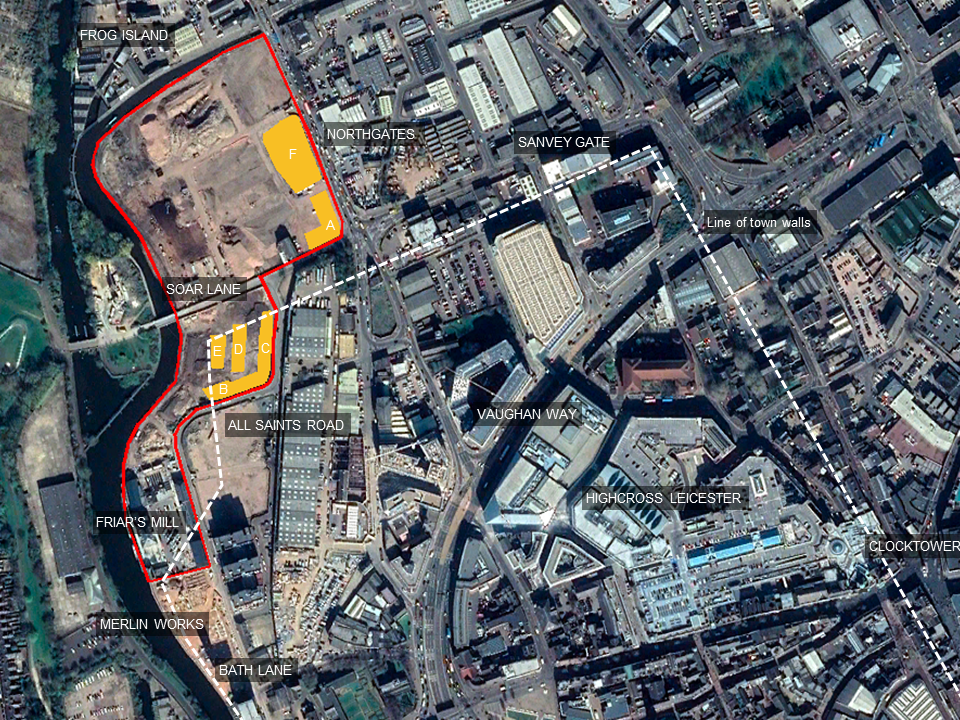

The characterisation phase of the work gave archaeologists an idea of what to expect beneath certain areas and the state of preservation and, following discussions with the City Council, those with potential were targeted for further exploration. Areas A-F yielded some incredibly well-preserved, significant and in some instances, unprecedented archaeological discoveries, providing a unique insight into Leicester’s and the nation’s Roman and particularly medieval past.

Roman regeneration

In many respects, the story of Leicester is one of continuous regeneration and this was readily apparent in a number of the Waterside areas. The earliest remains indicated that an affluent fringe of the Roman city was subject to significant redevelopment, perhaps on a municipal directive, nearly 2,000 years ago. A large building just north of Soar Lane (Area A), near the road (now Northgates) entering the Roman town from the north, was probably abandoned by the end of the 2nd century to make way for the construction of the town’s defences. At least five rooms were uncovered, the westernmost having an apsidal end. We know from the materials used and the substantial surviving opus signinum floors, that this was a well-built, high-status building, possibly a house for one of the town’s more affluent residents. Further analysis of the finds recovered, including the pottery may help us determine what the building was used for and refine the date of construction and demolition.

Further signs of disruption were apparent to the south along All Saints Road (Area B) where a substantial stone boundary wall, perhaps separating the garden of a Roman town house from the river, was likely to have been pushed over to facilitate the construction of the defences. Subsequently, the property it delineated was re-organised.

The Waterside (Areas B, C, D and E) is the latest of a number of sites that have given us a glimpse of the defensive network enclosing the town. Notable among these were Sanvey Gate to the east and Merlin works/Bath Lane to the south. Starting life in the late 2nd century as a series of large ditches fronting an earth rampart and a timber palisade, later replaced with a stone wall in the 3rd century, the defences were repaired, redug and added to through the Roman and medieval periods, and remained a visible feature in the city well into the post-medieval period.

Without seeing the whole extent of these substantial archaeological features, it can be difficult to determine their exact chronology. However, recent excavations have shed new light on the direction that the defences took in a corner of the ancient town where there was a gap in our knowledge. They were seen to follow roughly the line of the River Soar before turning and realigning to the street grid on an east/west projection and running parallel to and south of Soar Lane. The sequence of Roman and medieval ditches would have extended up to 30m from the wall, beneath present day Soar Lane meaning the Roman building excavated in Area A, must have been in the way and was demolished.

The medieval suburb

Just beyond the north gate of the town and along the road that led past the abbey to Nottingham and Derby, Leicester’s medieval north suburb was known from documentary sources. The work at Waterside, however, is the first to archaeologically examine it. The remains of floors and walls of seven medieval buildings fronting onto Northgate Street were discovered in Areas A and F. A number of these displayed unprecedentedly good preservation, particularly for buildings that, in contrast to the earlier Roman masonry buildings, were typically of more flimsey build. Walls made from a mixture of stone, slate, earth, clay and timber were common with crude beaten earth, or plaster floors. These had open hearths and flimsy internal partitions, and were repaired on an ad hoc basis.

Presumably regularly brushed, the floors produced few finds but sufficient material was recovered to point to an early medieval origin for the earliest properties, with a continuity of occupation through until the late medieval period, and a reduction of activity in the post-medieval period.

In the backyard areas were rough cobbled or metalled surfaces organised into longstanding ‘burbage’ plots extending back form the street and delineated by stone and clay boundary walls. The backyards would have been used for domestic and small scale cottage industry activities and horticulture. It is here that the importance of the material recovered from the pits, wells and surfaces lies. It is hoped that remains of plants, bones, and industrial residues, alongside the contents of rubbish pits and cesspits (drop toilets), will allow us to understand something of the lives and habits of the inhabitants and what they were doing in the buildings, be they shops, houses or small industrial workshops.

By the late medieval period the nature of one area of the site (Area F) had certainly changed with the appearance of a tanning industry, one of the earliest known manufacturing industries in the town. Animal skins were far more widely utilised 600 years ago, not just for clothing and footwear but for parchment, bottles and saddlery, to name a few items it needed preparing for. A series of somewhat regularly spaced rectangular and circular pits, some lined with clay with impressions for the staves of barrels or tubs imprinted, were recorded in the south of the area. These were very different to typical domestic refuse or stone-lined cess pits to the rear of the properties. From other sites in Leicester and elsewhere, fewer, more isolated examples of these have been interpreted as pits required for the different stages in the process of preparing leather, but it is unusual to discover the survival of such a concentration. The whole process would have included skinning, storage, cleaning and de-hairing of hides including ox, cow, calves and sheep, before the final stage of tanning, which preserves, waterproofs, and converts the skin to leather. The hides would be received and soaked in liquids made from unpleasant noxious substance including urine, brains and marrows. The nearby river and dug wells would have provided a source of water to enable this and it is likely its location in an increasingly derelict area of low-populated land on the outskirts of the city, outside the wall, where the stench could be distanced, was no accident. Chemical and environmental samples alongside skeletal remains of the animals used and the waste produced will both help to clarify this vitally important industry in medieval Leicester.

St Clement’s Church and the Blackfriars

The results of the Waterside excavations have much potential to provide new insights and expand our knowledge about the growth of the town and the activities that were undertaken, especially in an area that previously was little explored, but what about the people themselves?

On the south side of the investigation area, alongside present day All Saints Road, human remains were uncovered in Area B. This part of the town is the well-documented location of the Blackfriars, the Dominican friary, which may have incorporated the earlier Christian parish church of St Clements rather than building from scratch. The remains of a substantial building, represented by robbed foundation trenches extending beneath the present road, presented a good candidate for this. It was of little surprise that burials were discovered to the immediate north, aligned to, and respectful of, the building.

As careful removal of the human remains progressed one by one, it quickly became apparent that we were looking at a particularly interesting set of circumstances – 256 of the 454 burials were interred in mass graves. Medieval mass graves are rare, particularly in this country. In the burial pits, bodies were laid directly on top of each other in layers, with up to 23 bodies in a single grave. The remains were aligned east-west in keeping with Christian practice, with all ages represented (297 adults, 110 juveniles, 16 adolescents and 31 neonates). They clearly represented the aftermath of a catastrophic event, a famine or plague but our thoughts of the well- documented Black Death of 1349 were quickly dispelled when initial radiocarbon dating suggested that they were buried sometime between 1000 – 1100 AD, a date from which a single event of this magnitude is unknown. This will be refined with further samples but the evidence tallies with a series of entries in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles documenting widespread famine and disease during the 11th century.

“Afterwards came, through the badness of the weather, so great a famine all over England, that many hundreds of men died a miserable death through hunger.”

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, AD 1087

An additional 96 skeletons were buried in double graves – another unusual occurrence in medieval cemeteries. The osteological and scientific analysis (including ancient DNA and isotopic samples) will help determine sex, ages, pathologies and possible diseases, and we hope to be able to go some way to learning about the origins, lives, diet, health, illness and death of the people buried here.

We are still in the early stages of analysis during which specialists from around the world will be carefully analysing pottery, genetics, osteology and peering down microscopes at environmental remains and animal bones, to name a few. The discoveries at Waterside represent a fantastic, and in some respects an unprecedented, opportunity to answer questions we have about this corner of the city. It presents a chance to understand, not only the development of the town, the buildings, the way they were built and what was done in and around them, but to shed light upon the lives of the people who lived and worked, and ultimately died in them, people who may well be representative of those alive in towns in medieval England and further afield.

Source: ULAS